- WIADOMOŚCI

- KOMENTARZ

Rare earths, rare choices. Europe’s struggle to break free from China’s resource grip

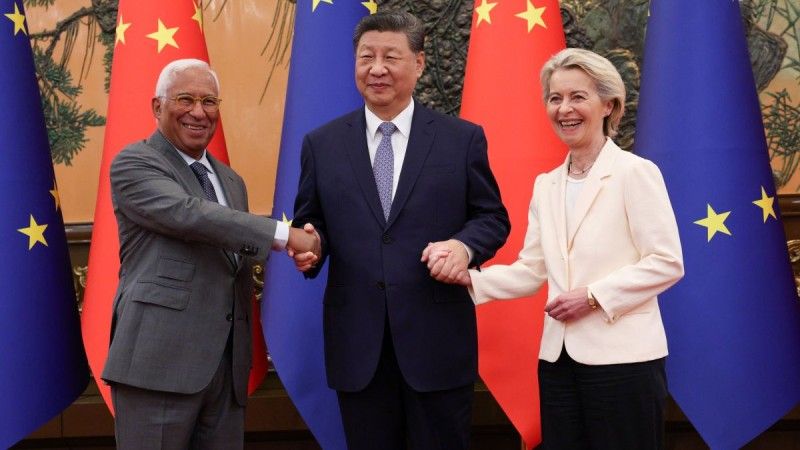

Rare earth exports have never been – and should never become – an issue between China and Europe. As long as export control regulations are followed and due procedures fulfilled, the normal needs of European companies will be guaranteed - assured Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi during a joint press conference in Berlin in July 2025.

Despite China’s reassurances, recent events have given rare earth export restrictions a far more strategic meaning. On 9 October 2025, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) officially announced an expansion of its export controls, adding five more rare earth elements (holmium, erbium, thulium, europium, and ytterbium) to the controlled list. The new rules extend not only to materials but also to equipment, technologies, and processes used throughout the value chain. The announcement introduced stricter licensing for products originating in China (effective immediately) and a new extraterritorial scope (to take effect on 1 December 2025), mirroring the US „foreign direct product rule”.

This explicit strategic lever has put the West on a high alert as fears over the security of critical supply chains intensify, especially within the defence sector. The United States is emphasizing »decoupling« efforts across key industries, with potential tariffs, countermeasures, and a push for accelerated investment, including a $1 billion US–Australian rare earths deal brokered on October 20. Meanwhile, European governments and industries are calling for faster diversification, the establishment of strategic stockpiles, and the advancement of strategic raw materials initiatives to secure its industrial base.

Yet Europe’s ability to safeguard its interests remains uncertain, as it faces the complex challenge of achieving a fully integrated supply chain in the West, a goal impossible to reach in the short term. What began as a trade policy has evolved into a geopolitical contest for resource control, with critical raw materials becoming a new Chinese weapon in the global power struggle.

China's strategic monopoly

Rare earth elements (REEs), a group of seventeen critical minerals, are considered the backbone of modern technology. Their dual-use nature makes them indispensable for both civilian and military applications, powering everything from electric vehicles (EVs) and wind turbines to high-performance magnets, lasers, and radar systems in advanced defence systems.

China’s dominance over the rare earth market poses a significant threat to Western technological edge and defence capabilities. Beijing currently accounts for around 70% of global rare earth ores and processes nearly 90% of the world’s REEs, giving itself control over almost the entire upstream and mid-stream supply chain. This monopoly means that every stage – from extraction and refining to magnet manufacturing and final component production – is largely dependent on China.

Recognising the strategic value of REEs, the Chinese government has already imposed export controls on twelve of the seventeen elements, designating them as strategic commodities and weaponizing them as a geopolitical tool. They have become one of Beijing’s most effective non-military levers, treating export licensing, quotas, and foreign direct investment in overseas mining projects as strategies used for economic protectionism and expanding its sphere of influence.

The geopolitical stakes: More than just trade

China’s actions are not only a reaction, but the execution of the priorities set out in its 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) – the strategy, in which Beijing has explicitly prioritisedsupply-chain security,technological self-reliance, andstrategic resource control. By tightening its grip on critical materials, China aims to reduce vulnerabilities in its own industries while using rare earths to extract concessions or gain bargaining power without resorting to military action, immunizing itself against global sanctions or supply disruptions.

This control extends far beyond materials themselves. China dominates the technologies, tools, and processes vital for refining and magnet manufacturing. Many of these are produced or used outside of China but still rely on Chinese-origin components. The latest export rules also give Beijing an extraterritorial reach, allowing it to use its policy as a powerful coercive tool. Xi Jinping’s administration could restrict foreign companies and global suppliers that use Chinese technology or inputs, even when production occurs abroad. Such measures strengthen China’s ability to dictate global supply chains, influence procurement decisions, and restrict access to critical technologies worldwide.

The Chinese strategy forces the West to pay the costly price for replicating Chinese-controlled supply chains, creating a dependency that Beijing can easily exploit. It is allowing China to set global prices, prioritise its domestic defence, semiconductor and EVs industries, and make substitution prohibitively expensive and difficult to scale. Imposing stricter control over global markets could also involve refusing exports based on vague or unspecified criteria. The new export licensing regime provides the ability to turn economic dominance into strategic deterrence without direct confrontation.

Europe in need of a dual strategy

The Chinese dominance of the rare earth market is not only an economic concern, but a national security one. With demand soaring across defence, semiconductors, and EVs sectors, this centralization places Europe in a vulnerable position. Any disruption to the supply chain, whether through export restrictions or trade disputes, could halt European manufacturing, delay weapons systems, and undermine NATO’s technological superiority, weakening deterrence across the alliance, and destabilising Europe’s immediate security environment.

Europe, which imported nearly half (46.3%) of its rare earth elements from China in 2024 and relies on China for over 90% of its rare earth magnet demand, urgently needs a dual strategy: short-term operational cooperation with the US and its other close allies, and long-term industrial autonomy. To bridge the gap between securing immediate needs and future self-sufficiency, Europe must combine joint action with rapid investment in its own extraction, refining, recycling, and substitution capacity. The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) represents a significant and proactive step towards securing the Union’s long-term stability, acknowledging the importance of raw materials, and recognizing them as strategic for the Union’s economic security and the green and digital transitions.

Yet for the European defence sector, the CRMA is an industrial policy and a strategic foundation, not a shield. Although its targets are vital, building mines, refineries, and magnet plants will take years. European defence companies therefore cannot afford to wait for the long-term strategies to take shape. They must act now by mapping critical inputs across all tiers of production, investing in domestic or allied refining capacity, certifying alternative materials, and setting up efficient recycling systems for magnets and alloys.

Companies that anchor joint ventures, secure multi-year offtake agreements, and coordinate well with NATO and EU on stockpiles will be the ones to weather the storm. Others will risk production gaps, delayed deliveries, and a rapid loss of technological advantage.

The clock is ticking...

Europe’s dependence on Chinese rare earths has already turned from an economic risk into an immediate strategic liability. The upcoming 15th Chinese Five-Year Plan (2026-2030), which is set to be revealed in a few weeks« time, is more than a policy document. It will likely reinforce Beijing’s broader upstream control over key materials, further strengthening China’s dominance across the mine-to-magnet chain.

Europe cannot afford complacency. Its reliance on Chinese-made components or materials embedded in critical defence technologies highlights the urgent need for the European industries to implement traceability and origin-of-materials rules to avoid unknowingly sourcing materials from politically unstable or untrustworthy suppliers.

The bottlenecks emerging across Europe’s critical supply chains underline a deeper challenge – one that goes beyond sourcing. It is about capability: the shortage of industrial know-how and workforce capacity in the refining, magnet production, and recycling sectors. Without heavy rare earth refining and circular recovery capabilities, Europe will be forced to continue to depend on Beijing for critical production steps. Furthermore, lengthy qualification processes and certification timelines for alternative sources only deepen that vulnerability, making it difficult for Europe to swiftly transition away from Chinese supply chains.

While the green transition and Europe’s defence ambitions unlock enormous opportunities, they also expose stark vulnerabilities. The European Commission has already taken decisive steps under the CRMA to address these risks and strengthen the continent’s resilience. Continued collaboration between industry, governments, and EU institutions will be essential to ensure that this momentum translates into lasting strategic autonomy.

European industries must therefore continue to build on this foundation and act decisively by accelerating transparency and traceability standards, stepping up investment in their industrial capacity, and anchoring strategic alliances to diversify supply beyond China’s chokepoint. By neglecting this progress, Europe risks deepening its material dependence on Chinese rare earths – this time, with even higher stakes.

Author: Karolina Chmielewska