- ANALIZA

- WAŻNE

- WIADOMOŚCI

Belarus between Washington and Moscow

America’s ongoing rapprochement with Minsk, Russia’s growing domination, and recent signals from Belarus have brought the old „Belarus dilemma” back to the table, reigniting debate over whether the EU and Poland should revisit their policy of isolating Lukashenko. Could limited re-engagement with the dictatorship prove beneficial for regional stability and Belarusian sovereignty?

The Western sanctions-dialogue cycle

Belarus’s relations with the West have long followed a cycle of freeze and thaw, driven by Lukashenko’s domestic actions. Repression and fraudulent elections brought sanctions and diplomatic breaks, while prisoner releases and limited liberalization reopened dialogue.

Washington largely mirrored this pattern: sanctions after the 2006 and 2010 presidential elections, then partial normalization in 2014–2015 as Belarus signaled greater independence from Russia. During the first Trump administration, normalization advanced further, marked by Mike Pompeo’s 2020 visit—the first by a U.S. Secretary of State in 26 years—and plans to exchange ambassadors.

This progress ended abruptly with Lukashenko’s violent crackdown on the 2020 protests. The Trump administration’s muted response contrasted with the EU’s tougher stance, as Trump himself notably stayed silent on Belarus. Joe Biden, by contrast, strongly backed the opposition and imposed sweeping sanctions. Subsequently, relations hit new lows after the arrest of Roman Protasevich, Belarus’s complicity in Russia’s war on Ukraine, and its hybrid operations against the West—cementing a transatlantic consensus on isolating Lukashenko and supporting Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya.

Washington breaks the isolation line

At the same time, Lukashenko’s decisions and the resulting political, economic, informational, and logistical isolation from the West pushed him further into Russia’s embrace to preserve his power. The Kremlin provided a lifeline for the regime, intervening during the 2020 crisis while effectively infiltrating Belarus’s state structures and imposing its Union State integration agenda. With Russian forces stationed on its soil, Belarus is now treated by Moscow as a „unified military space” and used as a platform for war in Ukraine and hybrid operations against NATO’s eastern flank. The country teeters on the edge of de facto annexation, and it is unclear how much autonomy Lukashenko retains.

This is the context in which the new Trump administration has broken with the policy of isolation, instead seeking rapprochement. The first signs appeared in January, when the U.S. Department of State quietly removed its statement on non-recognition of Belarus’s 2020 election. Lukashenko, likely sensing an opportunity for exchanging with a more pragmatic and transactional U.S. leader, released the first American citizen in late January.

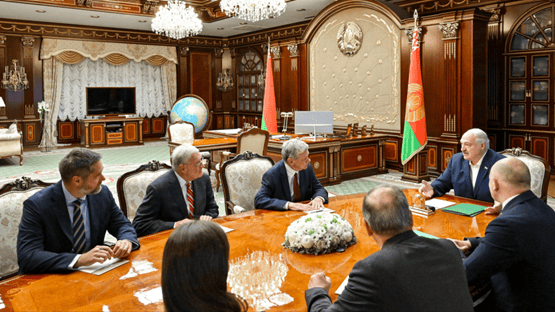

A sequence of diplomatic meetings ensued, effectively ending Belarusian isolation. In February, the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Eastern Europe, Christopher W. Smith, visited Minsk; in June, Lukashenko hosted Keith Kellogg, Trump’s special envoy for Ukraine. The negotiated deals were simple: easing sanctions for prisoner releases—Lukashenko’s trademark diplomacy with the West.

But the real breakthrough occurred when Trump made the first-ever presidential call to Lukashenko, just before meeting Putin in Alaska. In a subsequent Truth Social post, Trump referred to Lukashenko as the „highly respected President of Belarus,” thanked him for releasing prisoners, and expressed his intention to meet with the Belarusian leader.

This September marked the largest prisoner release to date, with 52 individuals freed. John Coale, Trump’s latest delegation head, described relations between the countries as „good” and outlined plans to reopen the American embassy in Minsk. Furthermore, the U.S. accepted Belarus’s invitation for American observers to attend the Zapad military exercises. Normalization is clearly underway.

America’s decision to re-engage with Lukashenko is a direct consequence of the administration’s softer stance toward Russia in its efforts to end the war in Ukraine. Here, rapprochement with the Kremlin naturally entailed rapprochement with Minsk. The U.S. likely concluded that Lukashenko will remain in power, making dialogue more beneficial than continued unfruitful isolation. Another factor in this equation may be Trump’s view of Lukashenko as a potential channel to Putin.

EU policy caught off guard

The American-Belarusian rapprochement caught the EU off guard, especially states neighboring the dictatorship: Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia. Despite the American shift, EU countries have maintained their policy of isolating the regime, while continuing to be the major center of support for the Belarusian democratic opposition based primarily in Lithuania and Poland. Brussels also continues tightening sanctions and tariffs on Belarus, with the latest round imposed this July.

In this context, the U.S. actions are undermining four years of Western-wide efforts by legitimizing Lukashenko and providing his regime with diplomatic and economic respite.

Recent U.S. moves concerning Belarus’s aviation sector have deepened these differences. Washington has partially eased restrictions on Belarus’s flag carrier following prisoner releases, restoring access to spare parts and technical services. At the same time, European sanctions continue to ban all such cooperation, leaving EU companies legally bound to deny similar assistance. This divergence highlights the growing gap between the American drive for pragmatic engagement and Europe’s rules-based approach. For Brussels, this episode also underscores how even tactical U.S. decisions can have strategic implications for European unity and sanctions enforcement.

Yet this comes after near-total isolation failure as well: the dictatorship is more entrenched and dependent on Moscow than ever.

Undoubtedly, the current EU policy suffers now from the lack of American coordination and successes, which may push Brussels to reconsider its approach, putting the old Belarusian dilemma back at the center.

The dilemma boils down to the question of what matters more: keeping Belarus away from Russia by letting Lukashenko maintain his balancing act, turning a blind eye to the regime’s violations, or trying to punish and break the regime through isolation, risking pushing it further into Putin’s arms. The values-oriented EU has traditionally leaned towards the second approach, prioritizing human rights and democratic principles over pragmatic geopolitical calculations.

Opportunities, risks, and uncertainties of re-engagement

Today, these harsh geopolitical realities are increasingly difficult to ignore: a dictatorship nearly absorbed by Russia, and an American re-opening already underway. Moreover, Belarus itself has already for some time expressed interest in engaging in dialogue with EU countries, also in actions, as among the recently released detainees were EU citizens, including one EU employee.

Therefore, there are strong arguments for and a real possibility of limited re-engagement. EU countries must carefully weigh what could be gained against what might be lost from such a move, especially those directly bordering the country.

In the most plausible scenario of limited diplomatic opening and partial lifting of sanctions, Lukashenko would gain more room to maneuver in his dealings with Russia and decrease its economic dependence on the Kremlin. That could allow the country to pursue a more independent and assertive policy towards Russia, perhaps returning to a more multi-vector foreign policy.

A clear sign of this new dynamic appeared in September, when Washington lifted restrictions on Belarus’s national airline as part of a broader political deal. The agreement restored limited access to Western-made aircraft components, but with strict conditions forbidding flights to sanctioned destinations such as Russia or Iran. In practice, the effectiveness of such limits remains doubtful, as the borders and logistics systems between Russia and Belarus are largely integrated. The development illustrates the strategic risks of partial normalization—benefits for Minsk may easily spill over to Moscow.

The downsides are obvious: legitimizing the dictatorship and weakening the democratic opposition-in-exile. This could be offset, at least partially, by pursuing „prisoner diplomacy,” leveraging engagement for mass releases—perhaps even of high-profile figures like Andrzej Poczobut.

In a more extensive dialogue, the EU could try to induce Belarus to cease or at least reduce its hybrid warfare against member states. The ongoing border migration crisis and repeated airspace violations would be priorities, as halting them would save significant resources. Another important objective would be limiting Belarus’s supporting role in Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.

The core threat of re-engagement lies in the possibility that it could be orchestrated and directed by the Kremlin. In such a case, it would yield only illusory benefits while strengthening Belarusian and Russian propaganda and economies. Belarus would likely become another channel for Russia to circumvent Western sanctions.

Yet maintaining or tightening isolation carries its own risks. For the sake of transatlantic coordination, re-engaging Americans would expect similar steps from their European partners, especially on prisoner releases and potential peace talks. Meanwhile, Minsk could exploit continued EU pressure by framing Brussels as escalatory while portraying itself as the side seeking dialogue.

The likelihood of this being a Russian plot depends on a crucial unknown: how much control over foreign policy and territory Lukashenko still maintains. If he has preserved some autonomy, Belarus might be partially disentangled from Russian influence and could offer valuable concessions regarding hybrid threats and human rights violations.

Thus, Western intelligence plays a crucial role in assessing Belarus’s actual sovereignty and willingness to engage in meaningful talks. EU leaders must also recognize the unchangeable limitations of the Belarusian regime: structural dependence on Russia, alignment with Moscow, and entrenched authoritarianism—these factors are non-negotiable. It is equally essential to establish clear red lines that cannot be compromised: preventing indirect benefits to Russia, maintaining support for the democratic opposition, and protecting Ukrainian interests in the ongoing conflict.

View from Warsaw and the eastern flank

The debate on such re-engagement is particularly acute in Poland today. In response to the Zapad-2025 exercises, Warsaw had closed land border crossings with Belarus, triggering significant disruptions in Eurasian trade. However, as of 23 September 2025, the border crossings have been reopened, following the state decision taken before the major drone incursions by Russia into Polish airspace. The reopening underscores that the closure was a temporary security measure rather than a sustained lockdown.

Interestingly, Belarusian forces reportedly warned Poland ahead of the drone incursion, which allowed for a faster and more coordinated response. While this gesture may be interpreted as a signal of Minsk’s interest in de-escalation and improved communication, it cannot be ruled out that the warning itself served a more technical purpose — prompting Warsaw to activate its air-defence systems near the border and thereby revealing radar coverage and reaction procedures. In the opaque environment of hybrid confrontation, even gestures of apparent goodwill may conceal elements of strategic probing.

At the same time, Washington’s current policy towards Minsk remains highly transactional. Should the political calculus in Washington shift — for instance, if President Trump concludes that outreach to Lukashenko no longer serves the broader objective of engaging Moscow — this thaw could end as abruptly as it began. The uncertainty surrounding both Minsk’s intentions and Washington’s consistency makes the entire rapprochement fragile and potentially reversible.

Lukashenko appears wary of the war spilling into Belarus, which would further erode his sovereignty and deepen Russia’s control. For the same reason, he may not welcome a total Russian victory in Ukraine or Moscow’s expanded influence in Europe. If true, there may exist an area of converging interests upon which both sides could build.

Should the political calculus in Washington shift — for instance, if President Trump concludes that outreach to Lukashenko no longer serves the broader objective of engaging Moscow — this thaw could end as abruptly as it began.

Following the 2020 election crisis, Poland—together with the Baltic states—holds significant, if not dominant, influence over EU relations with Belarus. This is why any idea of limited diplomatic opening must come from and be approved by these countries, as they are also the most exposed to the potential traps and risks of such renewed relationship. Warsaw thus faces a strategic choice: remain one of the strongest advocates of isolation, or cautiously test re-engagement under strict conditions. The stakes of this decision are high, encompassing both future regional stability and Belarusian sovereignty.

The U.S. re-engagement with Minsk illustrates that strategic patience may no longer suffice; regional actors must prepare for a post-Lukashenko Belarus sooner than expected. The United States is clearly seeking to improve relations with Belarus, signaling that Poland and other Eastern Flank countries must begin thinking strategically about their positioning toward Alyaksandr Lukashenko’s regime. This will not be an easy process, but it will soon become necessary. Despite its current dependence on Moscow, Belarus could, in the long term, become pivotal in drawing the region back toward the West. There is life beyond Lukashenko — and shaping that future should begin now.

Authors: dr Aleksander Olech, Kacper Kremiec