- WIADOMOŚCI

EU–India Free Trade Agreement: Will it deliver?

After nearly two decades, EU and India have announced the conclusion of negotiations on a Free Trade Agreement. The question now is whether this accord will prove to be a success?

The Impetus

The rationale behind an EU–India free trade agreement is straightforward. The European Union and India are democratic partners, like-minded on many issues, with economies that could complement each other across multiple sectors. Why, then, not dismantle or lower trade barriers? Both sides stand to benefit, strengthening stability in Europe, India, and beyond.

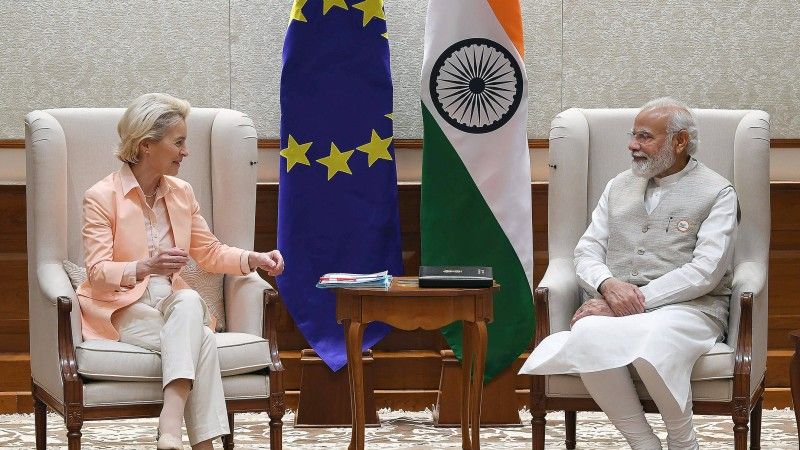

For years, however, these arguments – compelling though they were – failed to generate the political momentum required for such an ambitious undertaking. That changed in 2022, when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine upended the architecture of global trade and prompted a serious return to negotiations on EU-India FTA. The decisive catalyst, however, was the tariff policy of U.S. President Donald Trump. It was this development that drove intensive work on the agreement throughout 2025. The deal was formally announced on 27 January 2026, during a visit by EU leaders to New Delhi.

Politically, the agreement is undeniably a success. The more difficult question is whether this political achievement will translate into tangible economic gains, and whether the pact – hailed by Ursula von der Leyen as the „mother of all deals” – will have a meaningful impact on economic performance.

What the agreement contains

The final text has yet to be published and is currently undergoing so-called „legal scrubbing,” a process of technical and legal refinement. As such, any assessment must rely solely on information released publicly to date.

More detailed analyses are readily available online, but the core provisions are clear enough. The agreement introduces tariff reductions, dramatic in some sectors, largely cosmetic in others. For the EU, one of the most important areas is the automotive industry, where India had imposed tariffs of up to 110 percent. These are to be gradually reduced to 10 percent, albeit within a quota system whose limits are modest given the size of the Indian market.

Agriculture was a sensitive issue for both sides, and here there was broad consensus on the need to protect domestic markets. As a result, most of the sector will remain outside the scope of the FTA. An exception is highly processed European food products – chiefly sweets and chocolate – which pose little competition to Indian producers, given limited domestic production and modest demand. In this case, tariffs will be reduced to zero.

India, for its part, pushed for tariff reductions on textiles, leather goods, and achieved it, with EU tariffs in these sectors falling to zero. The same applies to furniture, chemicals, and base metals. In return, India will eliminate tariffs on machinery and electrical equipment, iron and steel, pharmaceuticals, and several other sectors.

Another sensitive area is mobility, or migration. The EU has agreed to establish a legal framework facilitating the movement of students and skilled workers, though ultimate authority will remain with individual member states.

On the same day in New Delhi, the parties also signed an EU–India Security and Defence Partnership, further reinforcing bilateral ties. This partnership spans a wide range of issues, including maritime security, cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, counterterrorism, the fight against organised crime, and space security and defence.

What does it all mean? Prospects and pitfalls

The agreement is indeed groundbreaking – particularly for India. It represents the most significant opening to foreign markets in the country’s post-independence history since 1947. Even after embarking on market-oriented reforms in the early 1990s, India continued to rely heavily on protectionism as a core economic principle. For the EU, by contrast, this is another free trade agreement, following closely on the heels of the Mercosur deal. Both sides hope it will generate an additional stimulus for economic growth.

The coupling of the FTA with a defense partnership aligns with the interests of European arms manufacturers eager to expand sales to India – a market already cultivated for years, most notably by French firms. While India remains dependent on Russian weapons, that reliance has been steadily diminishing. The combined effect of a defense partnership and an FTA could accelerate diversification of suppliers and, as European policymakers openly acknowledge, further reduce New Delhi’s dependence on Moscow.

Against the backdrop of strained relations – particularly for India – in negotiations with the United States, the FTA appears to offer both partners a convenient means of offsetting potential losses stemming from reduced profitability in trade with the world’s leading power. At the same time, both Brussels and New Delhi are keenly aware of the need to balance China’s role in global trade.

Will these hopes be realized? Or might the FTA generate new challenges, such as migration pressures or heightened competition from Indian goods on the European market?

Based on the information currently available, and in the absence of the final text, it seems unlikely that such negative effects will materialise in the near term. More plausibly, the phased reduction of tariffs will not unleash the kind of business frenzy its architects anticipate. The agreement may therefore prove to be more significant politically than economically. It will undoubtedly facilitate bilateral trade and deliver tangible benefits, but probably on a smaller scale than suggested by the optimistic rhetoric of Ursula von der Leyen and Narendra Modi.

As for potential downsides, it is simply too early to judge – particularly given that the final wording of the agreement has yet to be made public.