- ANALIZA

- WIADOMOŚCI

- WAŻNE

The wave of defence bilateralism in Europe: a cause for optimism?

European defence bilateralism is booming. According to a recent report by the German political foundation Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, as many as 135 bilateral defence agreements have been signed across Europe. This accounts for 80% of all agreements (including plurilateral ones) concluded since 2014. Moreover, 2024 and 2025 have seen the highest number of such agreements, which, according to the report’s authors, reflect growing concerns about Donald Trump’s return to the White House.

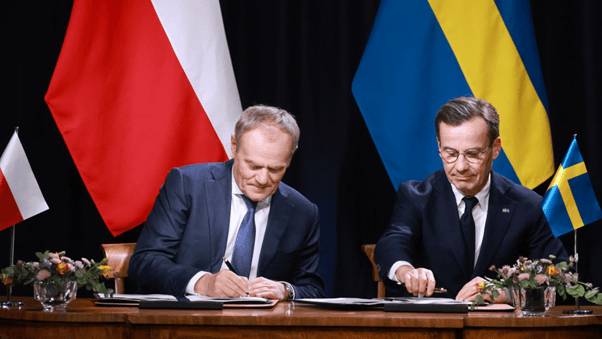

France, the UK, and Germany top the list, with 31, 25, and 24 agreements signed, respectively, since 2014. Close behind is Ukraine with 23, followed by Poland and Sweden (18 each) and Finland (13). At the bottom of the ranking are primarily countries of Southern and Western Europe, as well as Hungary. Notably, most of these agreements are comprehensive in scope or concern procurement and industrial cooperation, while only six focus specifically on cybersecurity.

The authors of the report interpret the sharp increase in bilateral agreements across the continent as a positive trend. These partnerships are seen as a means of strengthening defence ties between states in the face of the threat from Russia and concerns over the US withdrawal.

That said, they also warn against the lack of coordination, which could lead to duplication and inefficiency, and in turn fuel the very fragmentation that the European Union is currently seeking to overcome. They further note that some of these agreements may be largely symbolic, serving mainly a political function rather than delivering tangible new outcomes.

It appears that the growing number of bilateral agreements stems from differences dividing European states and their resulting divergent needs, which often make it difficult to conclude multilateral arrangements. Data from the report reveal a clear correlation between the number of bilateral agreements and both the size of a country’s defence industry and its geographic proximity to Russia. Countries with well-developed defence sectors undoubtedly see an opportunity to secure lucrative contracts with nations that feel particularly threatened.

Meanwhile, among the countries that share a similar threat perception from Russia, clear regional clusters of defence cooperation are emerging — this is particularly visible in Scandinavia and the Baltic states. Interestingly, Poland’s network of agreements shows a high degree of diversification, encompassing both neighbouring countries in the region and larger states in Western Europe.

However, it is Ukraine that has developed the most diversified network of agreements, having signed deals with almost every European country. This points to Ukraine’s growing integration within the European defence system, with recent agreements shifting from merely providing assistance to Kyiv toward facilitating European access to Ukrainian defence technologies and industrial base.

In the coming years, the pace of signing new agreements may naturally slow down due to the limited number of potential partners and areas for cooperation. The true measure of success for this wave of bilateralism should not then be the sheer number of agreements concluded, but their tangible outcomes, such as joint procurement, technology transfers, or enhanced interoperability.

Ideally, the current wave of bilateralism will serve as a cornerstone for broader multilateral initiatives, which could eventually be implemented at the European or NATO level. The defence agreements concluded today should not mark an end, but the beginning of a new phase of European defence integration.