- ANALIZA

- WIADOMOŚCI

Premium Treaty? France, Poland, and the Game of Interests

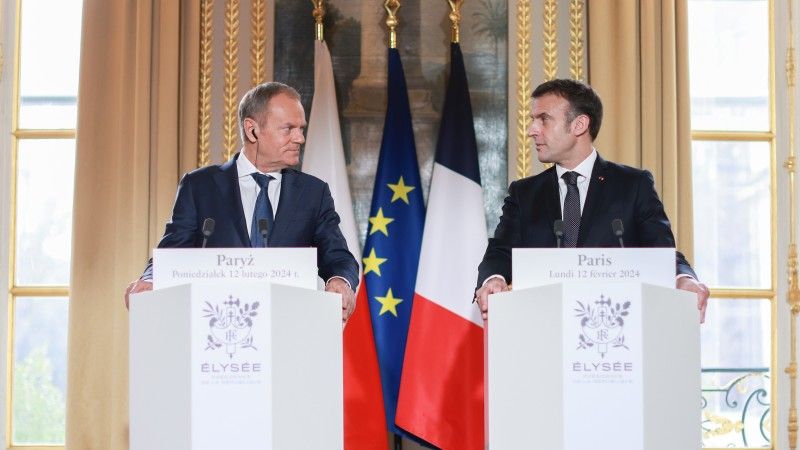

On 9 May 2025, a treaty of friendship and cooperation between France and Poland will be signed in Nancy. It is worth considering what significance this may hold and why it should be approached with moderate enthusiasm and common sense.

This event coincides with Europe Day and, significantly, after the weakening of cooperation along the Paris–Moscow line, with Russia’s Victory Day. The previous treaty was signed on 9 February 1991, when France supported Poland’s aspirations to join NATO and the European Union. Now, bilateral cooperation is to be elevated to the level France has so far maintained only with Germany, Italy, and Spain. Although the agreement is strategic in nature and many actions are yet to begin, building an alliance with another nuclear power is meaningful. Diversifying relations and seeking new solutions to strengthen Poland’s security remain key in the context of the war in Ukraine. However, one should not fall into blind optimism, as France remains a highly pragmatic state—but President Macron’s opening towards Central and Eastern Europe is an opportunity worth seizing.

France has signed strategic treaties of friendship and cooperation with Germany (the Élysée Treaty of 1963 and the Aachen Treaty of 2019), Italy (the Quirinal Treaty of 2021), and Spain (the Barcelona Treaty of 2023). All of these agreements are „premium” in nature—they cover broad political, economic, educational, cultural cooperation, as well as matters of security and defence. They provide for, among other things, regular intergovernmental consultations, joint industrial initiatives, scientific collaboration, and coordination of international actions—including in security policy, defence, and European policy.

In the case of the United Kingdom, France signed the so-called Lancaster House Treaties in 2010—among the deepest bilateral defence agreements in the world. These include joint expeditionary forces, cooperation on nuclear weapons, defence technologies, and cybersecurity. In 2023, an additional agreement was signed concerning the protection of shipping and port infrastructure. Although the UK does not have a classic „friendship treaty” with France, their cooperation in the field of security is exceptionally advanced and enduring.

The „Treaty of Nancy” is a historic step and a symbolic moment, as Poland joins the elite group of France’s closest strategic partners in Europe. Just like the earlier agreements with Berlin, Rome, and Madrid, the new treaty with Warsaw will cover cooperation in defence, industry, energy, education, and joint European policy. It is an expression of mutual trust and a recognition of Poland’s growing role as a key pillar of stability and security on the eastern flank of the European Union and NATO.

At the same time, it must be emphasised from the Polish perspective that there is a lack of an element that would give Poland a stronger partnership than the others. Perhaps, if the components of the upcoming treaty are indeed implemented and France proves to be a consistently reliable partner, another agreement may be signed in a few years in Pułtusk (a city historically significant for our relations). Moderate „Franco-optimism” is justified, although the real opportunities for cooperation are only now beginning to emerge.

Macron’s Evolution

Emmanuel Macron’s policy towards Russia has undergone a clear shift. In the early years, Paris attempted to build a relationship of strategic dialogue with Moscow, reflected in meetings with Putin and calls for rapprochement. All of this changed after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. France began to provide tangible support to Ukraine—supplying equipment, training soldiers, and increasing its involvement on NATO’s eastern flank. In addition, cooperation with Estonia, which had long warned of the Russian threat, became a practical response, as did joint exercises with Finland. Paris prioritised military presence, joint drills, and experience-sharing.

At the same time, France was pushed out of the Sahel. Military coups and growing Russian influence led to the end not only of military operations in the region but also a complete withdrawal from Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. France lost influence it had previously regarded as strategic. In a different direction—in relations with Armenia—Paris increased political and military support, which negatively affected ties with Azerbaijan. At the same time, Macron is seeking to maintain a dialogue with Turkey, understanding its importance for international security. The French President has not abandoned his ambitions to be a security leader in Europe, advocating for European Union autonomy—a stance not aligned with the United States. Yet Macron’s efforts remain mostly aspirational, as seen in the situation in Ukraine, where Kyiv remains fully dependent on Washington.

What’s problematic is that Macron has only two years left in his presidency. His entire evolution—from moving away from rapprochement with Russia to actively supporting Ukraine—could be abruptly cut short by the upcoming elections in France. He has not yet named a successor with a real chance of winning. Even a potential disqualification of Marine Le Pen, currently leading in the polls, wouldn’t change the picture dramatically, as Jordan Bardella is already campaigning and holds a strong position. The Left also remains in play, having gained strength after the last parliamentary elections. There is therefore a risk that the treaty signed today and the dynamic implementation of its provisions could stall in two years« time.

That’s why both sides must achieve as much as possible in the shortest time available, while there is still a shared determination to cooperate and common challenges—above all, the threat from the Russian Federation. Macron’s evolution must not be wasted, because France’s current policy toward Poland is the best it has been in the 21st century. Everything now depends on both governments—French and Polish. Let’s hope that domestic politics, as has so often happened on both sides, does not destroy what is truly important today. In recent years, both President Duda and Prime Minister Tusk have spoken of cooperation with France in very similar terms.

Buy Our Weapons

France’s approach to defence cooperation may prove problematic. At present, Paris is primarily focused on selling arms—including to Poland. It’s important to note, however, that Warsaw is already pursuing one costly „strategic partnership,” and further weapons purchases in exchange for security declarations are not enough. The treaty outlines many more areas of cooperation, and it’s there that a balance of benefits for both sides should be sought. If France were to purchase from Poland, it would likely be in a limited capacity—but the Piorun air defence system would undoubtedly be a valuable addition. For now, the French offer—while not without flaws—remains worth watching. Antoni Walkowski from Defence24 shares his opinion below:

„One of the most pressing problems facing the Polish Armed Forces is the inability to produce artillery ammunition domestically in large quantities, as well as the lack of expertise in multi-base propellants used in modular charge systems. Here, companies like KNDS Ammo France and Eurenco—leaders in this field in Europe—could come to Poland’s aid. Ammunition offered by the French defence industry is modern and has development potential. Furthermore, Eurenco offers insensitive propellants, and KNDS Ammo France includes in its catalogue the KATANA precision-guided munition, the BONUS anti-armour sensor-fused munition, and SPACIDO trajectory correction fuzes. For good reason, France is seen as a front-runner in Poland’s ammunition programme.

One of the most important Polish procurement efforts involving French defence companies is the Orka programme. The Scorpène diesel-electric submarines proposed by Naval Group for the Polish Navy offer several significant advantages. Scorpène is a wholly French product, and thus not subject to third-party export approvals. Moreover, its systems and armaments—including combat systems, sonar, optronics, heavy torpedoes, anti-ship and cruise missiles, mines, and drones—are all French-made. This gives France full autonomy in selling fully equipped, still-modern vessels to any country in the world, including Poland.

The issue, however, is that Scorpène is one of the oldest designs in the Orka programme. While the Scorpène Evolved variant recently sold to Indonesia will include lithium-ion batteries from Saft, the air-independent propulsion system FC2G developed by Naval Group has yet to find a buyer. Scorpène is also purely an export product, not used by the French Navy or any other European navy. This means that, should Poland purchase it, there would be limited interoperability between the Polish Navy and the French Marine Nationale. The chances of Poland being offered the newer Blacksword Barracuda submarines—recently purchased by the Dutch Navy—seem very low, and their expeditionary design would be poorly suited to the shallow Baltic Sea.

The French defence industry also presents an interesting offer in the aerospace sector. The Airbus A400M Atlas transport aircraft is still a relatively new platform with considerable upgrade potential and approximately twice the payload capacity of the Hercules aircraft currently operated by the Polish Air Force. However, due to the nature of the threats facing Poland, acquiring aircraft of this class appears to be a low priority. The cost of purchasing and maintaining the Atlas also raises some questions. Airbus’s promotional efforts may be seen as an attempt to compensate the European manufacturer for reduced A400M orders from France and Germany.

In contrast, when it comes to aerial refuelling aircraft, the Airbus A330 MRTT is the undisputed favourite among Polish analysts. Put simply, it is the best aircraft in its class—operated worldwide and produced in series. Moreover, its only real competitor, the Boeing KC-46A Pegasus, continues to face numerous unresolved issues. The A330 offers greater payload capacity and can carry more fuel. In addition, the MRTT continues to evolve; soon, it will be based on the newer A330neo rather than the A330-200. The new MRTT variant will have greater range, boosting the capabilities of the European tanker while leaving the Pegasus far behind.

Poland’s interest in acquiring cruise missiles should also not be forgotten. Last year, the French branch of MBDA publicly unveiled the LCM missile—a land-based version of the naval MdCN system. This weapon is being offered as part of the European ELSA programme, which aims to give its members deep-strike capability. In this area, France possesses a breadth of expertise unmatched by any other European country. It is therefore worth following developments related to the LCM system and other missile projects involving French industry—such as the Franco-British FMAN/FMC.

Poland is also expected to consider expanding its involvement in the Pléiades Neo satellite programme, led by Airbus Defence & Space, as well as other joint space initiatives. However, I will refrain from commenting on that here and refer interested readers to articles by our colleagues at Space24.pl.

Unfortunately, Poland has much less to offer France than vice versa. Paris has become the world’s second-largest arms exporter for good reason. „Fabriqué en France” is not just a matter of protectionism or national sovereignty in defence—it’s also a highly profitable investment. This is particularly true for high value-added products such as Rafale multirole fighter jets or CAESAR howitzers. It’s hard to fault France for its effectiveness, though I fear that potential French-Polish defence cooperation may be quite one-sided. That could change if the Armée de terre were to acquire new tracked armoured vehicles or purchase thousands of Polish-made drones and man-portable air defence systems. But there’s no indication that such a move is likely.”

French Pragmatism

The topic of the presence of the French Armed Forces in Ukraine remains relevant, even if it has clearly faded from the spotlight in recent weeks. It is one of many initiatives from President Macron that initially garners international attention but then temporarily disappears from view. From the outset, Poland has made it clear it will not deploy its own contingents, yet it still remains a central hub for the entire operation—just as it has been for Ukraine and all those aiding or establishing a presence there since the war began.

Our role deserves recognition, but we should also begin leveraging the fact that we are one stop further east. It must be acknowledged that Paris’s primary objective in building its position is not cooperation with Warsaw, but with Kyiv. France wants to expand its capabilities and invest in Ukraine, already thinking about the post-war period. One might get the impression that Franco-Ukrainian relations in recent months have been better than Polish-Ukrainian ones.

France makes no secret of its preference for diversifying alliances. A prime example is its close relationship with India, where arms sales are worth tens of billions of euros—even though New Delhi maintains robust resource ties with Moscow. Other key partners (where Russia remains in the background) include the United Arab Emirates (which purchases French arms and hosts French troops), Egypt (with a Russian-built nuclear power plant and Russian weapon systems), and Armenia (long connected to Moscow and hosting Russian military bases). Cooperation also continues with China, Kazakhstan, and Serbia. Paris views alliances globally, and only the naive would assume that a treaty with Poland automatically means abandoning other relationships that are simply too lucrative for France.

Even the notion of exclusive treaties and elite clubs is not entirely accurate. In addition to the upcoming May 9, 2025 agreement with Poland—following earlier treaties with Germany, Italy, and Spain—France has signed several other defence-related agreements this year. In January 2025, France and Norway signed a letter of intent for defence cooperation covering joint exercises, critical infrastructure protection (including undersea cables), and the development of military equipment. In March, an Indo-Pacific Security Agreement was signed with Indonesia, expanding collaboration in the Asia-Pacific region.

Paris and Washington’s expectations also include military aspects. Just as the United States leads many international operations, France has been involved in military missions for years. Notably, it has drawn in close partners—such as Estonia in African operations. It’s not out of the question that future defence cooperation will include joint overseas missions, especially since joint military exercises have long been underway.

In the Franco-Polish tango, there’s also a third interested party. The new German chancellor is set to visit both Warsaw and Paris, and the Weimar Triangle format regularly re-emerges on the agenda. It’s important to remember that France also sees Poland as part of its strategic manoeuvring with Germany. On the one hand, it demonstrates an ability to collaborate with other partners; on the other, it continuously underscores that its relationship with Berlin is crucial to EU stability. In this triangle, vigilance is key.

It’s possible that France will look very different in a few years—perhaps in ways that won’t appeal to Poland. That’s why it is so important to learn from others and adopt the methods our allies use. In this case, bilateral ties should be strengthened—but with the assumption that we must not fully subordinate ourselves to them. France is one of many partners for us, just as Poland will be one of many for Paris.

No one expects the French to defend Polish borders in Suwałki. Still, they maintain a presence in Estonia and Romania, where cooperation is going well. Until the moment comes to say „prove it,” the alliance may feel uncertain. That’s why it’s worth taking advantage of every element surrounding this treaty, which covers much more than security. Nothing prevents Poland from developing relations with other partners and strengthening its own military capabilities.

The treaty’s signing location is also noteworthy. Unlike the previous three agreements (with Germany, Italy, and Spain), which were not signed on French soil, this time—for the first time—it will be. Marcin Giełzak fromDwie Lewe Ręce points out: „Choosing Nancy as the place to sign the treaty is unfortunate. The legacy of Stanisław Leszczyński, a bankrupt Polish king turned French client, doesn’t evoke the best associations. For Paris, the War of the Polish Succession meant territorial gains and enhanced influence. For Warsaw, it marked the final confirmation of lost sovereignty on the international stage.”

Let us ensure that this is the only reference to that unfortunate patron of the treaty. The Republic of Poland must not assume the role of a „buyer of security,” paying in hard currency—defence contracts, major investments, or consent to boosting France’s position in the EU at the expense of countries like ours—in exchange for verbal assurances or symbolic troop deployments. Macron is no less transactional than Trump; if he senses weakness, he will exploit it. Ideally, we should model our future relations with France after India, which adheres strictly to the quid pro quo principle: every deal with the French is a package transaction, carefully protecting its own agency in the relationship. Of course, we do not have the geopolitical weight of the Indian subcontinent and cannot be equally effective, but we have a duty to extract as much as we can. We must unlearn the bad habits from the time when we were merely an EU candidate state and naturally yielded to those deciding whether to let us in.

Now, as a full-fledged EU member and a key country on the eastern flank of both the EU and NATO, we can demand more equal treatment. Moreover, we should fully capitalise on the favourable circumstances brought about by France’s anti-Russian pivot. Paris—at odds with Moscow in Africa, the Caucasus, and Central Asia—is becoming an arms supplier to Putin’s neighbours. It is a partner worth talking to. In the context of France’s deepening cooperation with countries like Kazakhstan, the notion of France as a „provider of sovereignty” to former Russian spheres of influence is being openly discussed. However, this shift need not be permanent or maintain its current intensity. A future far-right or far-left government in France might, but doesn’t necessarily have to, pursue détente with Russia. Acting while Emmanuel Macron is still in the Élysée and while policy is grounded in facts seems like a sensible path forward.

Elevating the relationship to a „premium” level is significant and opens up a range of opportunities. At this moment, we must strike a smart balance between General de Gaulle’s assertion that „States have no friends, only interests” and Emmanuel Macron’s vision that „Europe must see itself as a power, a shared destiny and a common project.”

Don’t Look Back

A difficult history did not stop Poland from offering help when it was simply needed. Despite the memory of Volhynia, Poland was the first to support Ukraine after the Russian invasion, showing remarkable commitment. We became—and continue to be—a logistical, political, and military backbone for Kyiv. At the same time, hybrid operations by the Russian Federation are ongoing, and the situation on the Belarusian border remains highly tense. We also have our own complex history with Germany. It is our largest economic partner, but that does not mean that issues such as reparations or historical truth can be brushed aside. We expect a response.

We demand a respectful approach from Kyiv toward Polish victims and the right to conduct exhumations. We also have every right to expect Berlin to take an interest in matters that remain unresolved. In international relations, memory cannot be one-sided. There must be accountability for past actions, as they are the mirror image of present-day expectations.

France, too, understands these tensions and misunderstandings, particularly within Polish society, because it has itself been both witness to and cause of many unfulfilled promises. In 1939, it had a binding alliance with Poland—confirmed just before the outbreak of war—but limited itself to passive observation and failed to fulfil its military obligations. Today, under the new treaty, grand words are being spoken about partnership and shared values. But partnership is not about declarations—it is about decisions made in critical moments.

If Paris truly wants to build a united Europe with Warsaw, it must understand Poland’s sensitivity to security, history, and sovereignty. This is not about politeness or political gestures—it’s about reciprocity. That is the simplest test of a reliable ally. Today, we have NATO, and we have a strong partner in the United States—France should be an additional reinforcement of our expectations.

Security Guarantees Yes, Nuclear Deterrence No

In addition to numerous treaty provisions important for bilateral relations—from political issues to energy, education, and cybersecurity—one of the key pillars of Poland’s deepening cooperation with France is security guarantees. This additional support from Paris could prove crucial in the face of threats from the Russian Federation. It is a valuable component that, in the midst of the ongoing war in Ukraine, complements the autonomous European strategy that has been evolving in recent months. For Poland, situated on NATO’s and the EU’s eastern flank, every additional security guarantee carries real weight.

At the same time, all illusions regarding potential nuclear guarantees from the French Republic for Poland must be dispelled. To date, there have been no agreements or arrangements that cover such commitments—not even with the United Kingdom, with which France cooperates in nuclear security. In this area, France remains entirely independent and sovereign. Its nuclear doctrine focuses on deterrence rather than the active use of nuclear weapons. These weapons are considered the ultimate guarantee of national sovereignty and a safeguard for so-called vital interests intérêts vitaux).

The decision to use nuclear weapons lies solely with the President of the Republic. In the speeches of successive French leaders—especially Jacques Chirac, Nicolas Sarkozy, and Emmanuel Macron—it has been repeatedly emphasized that a nuclear response might be considered in the event of a threat to the state’s vital interests. This applies not only to attacks involving weapons of mass destruction but also to conventional weapons if their consequences are severe enough. France does not adopt a doctrine of automatic first use but does allow for a nuclear response even if the adversary has not employed nuclear weapons.

The concept of nuclear sharing is not on the table for France. Nor is there any realistic possibility of a permanent deployment of French submarines in the Baltic Sea or a standing Rafale mission over Poland. Any such „permanent presence” would require massive infrastructure investments, a complex logistics chain, and appropriate security conditions. This is a long and expensive process, and in France’s current political position—especially under President Macron—remains an unrealistic scenario.

However, should Poland face a serious threat from the Russian Federation, the activation of so-called deterrence dialogue would be possible. This does not imply a necessary use of nuclear weapons but could include the deployment of French forces—for example, in a temporary Rafale fighter mission. Why would that be feasible in such a case? Because it would involve a real threat to French interests, as France also maintains strategic objectives on NATO’s eastern flank. This is where the fundamental difference with the U.S. lies: France, being in Europe, directly feels the threat to its own interests. Thus, French Rafales—fully capable of carrying nuclear missiles—could, if needed, be used as part of allied deterrence, without transferring nuclear weapons to any other state. The presence of „nuclear-capable Rafales” in Polish skies, even as part of a short-term mission, would be critical in such a scenario.

The French are uncomfortable with the term „nuclear umbrella” because it implies that the one „holding it” automatically becomes a target. Their perspective is more about providing support within a deterrence strategy—not about directly assuming risk on behalf of others.

France has also expressed interest in greater allied participation in deterrence-focused exercises and manoeuvres, during which its armed forces could demonstrate readiness and credibility. The goal of these activities is not only to enhance interoperability but also to show partners what modern nuclear deterrence entails and how it can contribute to Europe’s defence. This also presents a potential opportunity for the Polish Armed Forces to take part in such exercises.

Paris expects Warsaw to take an active role in seeking shared military interests with France. Only on this foundation can the concept of „European deterrence” be further developed. In this context, it is increasingly emphasised that a better path than developing a nuclear umbrella would be to strengthen conventional capabilities—for example, through the development of ballistic or cruise missile systems.

A Roadmap for a Long Journey

It would not be an overstatement to say that the treaty being signed is not only a signal to Russia. It is also a message to the United States: Poland can have other nuclear allies who offer their own security guarantees. NATO remains the foundation, complemented by American involvement, but in the context of the treaty, expectations are also directed toward the French. Naturally, some will say these are just „paper guarantees,” but there’s no doubt that it is better for Poland to have multiple nuclear powers engaged in cooperation.

What matters most about the treaty is everything that happens after—and beyond—it. Many elements, intentions, and plans can be written into the document, but in practice, it serves simply as a roadmap for the coming months. The signing itself will be a grand affair, with references to shared history and declarations of numerous areas for collaboration from both countries« leaders. However, the actual work begins the next day. Public administrations, private sectors, and NGOs must receive a clear signal from their governments—both French and Polish—to intensify their efforts. I have seen dozens of such agreements signed, and what always matters most is what follows. A treaty is the highest form of international agreement. Once signed and ratified (the parliamentary votes will be worth watching), it becomes legally binding, and both countries are required to honour it. At the same time, the manner of its implementation, the intensity of cooperation, and the expansion of specific areas are up to both sides.

France already has experience in agreements of this kind. In 2019, it signed the Treaty of Aachen with Germany, which was theoretically intended to deepen cooperation in foreign policy, defence, and arms industry development. One of its key provisions was a commitment to jointly develop weapons systems, including the next-generation MGCS tank and the future FCAS multirole aircraft. However, both projects quickly encountered serious obstacles: divergent industrial interests, disputes over the division of responsibilities, and differences in pace. The newly created Security and Defence Council did not change the reality that both countries continued to pursue independent policies.

The symbolic nature of Aachen did not translate into a real breakthrough. Tensions also arose in defence and energy policy—especially over nuclear power, where France is a strong advocate and Germany a determined opponent—along with further delays and misunderstandings in joint military projects. A coherent strategy for global challenges is also lacking: the two countries differ in their approaches to China, the U.S., Africa, and Israel, and have different timelines for EU reforms such as enlargement or budget issues. Therefore, if a similar treaty is to be signed between France and Poland, it would be wise to distinguish media gestures from actual, effective mechanisms of cooperation in advance.

France is currently grappling with major internal challenges: illegal migration, rising crime, social tensions, and political crisis. After early elections in 2024, Michel Barnier’s government fell to a vote of no confidence, and the new cabinet under François Bayrou now functions as a minority government with one of the lowest approval ratings in history. The budget deficit exceeds 5.8% of GDP, public debt is over 112%, and the consequences of the pension reform continue to spark protests. Widening polarisation and tensions around migration are further destabilising the situation. It must be said that internal weakness translates into external weakness. France must evolve during Macron’s remaining two years in office, as its current circumstances limit its ability to develop international cooperation. The treaty with Poland is important—but an open question remains: how much of a real priority will it be for France?

Kacper Kita ofNowy Ład, author ofThe Saga of the Le Pen Family, concludes: „Public sentiment in France over the past three years has clearly shifted in an anti-Russian direction—as reflected in both public opinion surveys and the positions of all major political parties. Aside from the far left, no one criticises increased defence spending. Combined with growing disappointment over developments in Africa, the great-power ambitions of the French, and President Macron’s desire to escape domestic problems through active diplomacy (the only area where he enjoys broad support from both the public and political class), this creates a window of favourable circumstances for Poland—which we should not waste.

A sensible diversification of our directions in military and other forms of cooperation would be wise if we want to be perceived as a serious player—whether in Washington, Paris, or elsewhere. At the same time, we must have no illusions—France cannot replace the U.S.; it lacks the capacity and is burdened by high and rapidly growing debt. However, it can be a valuable complementary partner. We should realistically and gradually increase its involvement in our region, which for decades was of little interest to the French but is now more present in their public discourse—just like the view of Poland as a growing power worth reckoning with, sometimes even excessively positively.”

Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly is said to have remarked: „Poland is a romantic heroine, always standing proudly despite the blows of fate.” I believe we’ve endured enough of those blows. This agreement with France, along with the associated security guarantees, should serve as an additional shield for the future. Enough talk and rising expectations—it’s time to act. May 9 in Nancy will be forever inscribed in the history of Polish-French relations. It is „just” and „more than” a treaty, one that presents Paris and Warsaw with a host of challenges. For anyone who truly hoped for a fresh start in relations in the 21st century, now is the moment. Ready-made projects and initiatives are scarce, and the hardest part lies ahead: developing this „premium” relationship over the coming years and through successive governments. Poland and France can stand shoulder to shoulder and face the challenges posed by Russia and Ukraine together.

Good luck.Bonne chance!

Author: Dr Aleksander Olech; Contributors: Marcin Giełzak, Kacper Kita, Antoni Walkowski